One Fathom Deep is a show of paintings and drawings at the Northlight Gallery in Stromness throughout April and early May 2025

One Fathom Deep is a show of paintings and drawings at the Northlight Gallery in Stromness throughout April and early May 2025

For many artists their relationship with the studio is a complex one. A studio can mean different things at different times. The studio is often the place of invention, the place of escape and sanctuary, a lonely place, a desert, definitely a fridge, a kitchen, an oven, a torture chamber and talking of chambers, what about the echoes in there too?! It is also a storeroom, where work, materials, and tools accumulate and stand around, waiting for me to act, like Betjamin’s ‘munching by-standers, who offer nothing’*.

The studio is like an ante-room, a corridor, between one door and another. The long corridor of the mind even, down which thought heads optimistically for the door and returns prejudiced by experience. The corridor is an apt metaphor in another sense too; it is the place where worthy art goes to hang out. Largely unnoticed, sited in a place of transit for others to commute through on their own daily journey between the internal and external worlds.

It’s a curious thing, but just before I go back into the studio the day after working on something, I can’t remember what it looked like when I left it. Paradoxically, this forgetfulness offers a precious, but short-lived moment of clarity. When I walk in I see it properly, as it really is, before the over-bearing-problem-solver in me regains control and marches me back down the corridor of uncertainty, as Geofrey Boycott might say.

Generally speaking, In the studio I oscillate between three lines of enquiry, all distinct and seemingly resistant to curatorial cohesion. I can’t seem to settle on just one, which is a bit awkward for a painter (discuss) perhaps I do it through lack of conviction, or because it’s a failsafe? On the other hand, I’m no scientist, but isn’t the antithesis of the oscillating wavelength probably the flat line? Nobody wants to flatline do they!?

Anyway, all of this is academic, because in recent times I have ducked the issue completely and taken my paints outside to work instead. So what is outside then? Well, balance, or actually I mean imbalance, or let’s call it redressed balance: more external experience and less introspection (c.f. virtual), which seems about right for me presently.

*I think it was Betjamin, but I might have paraphrased him

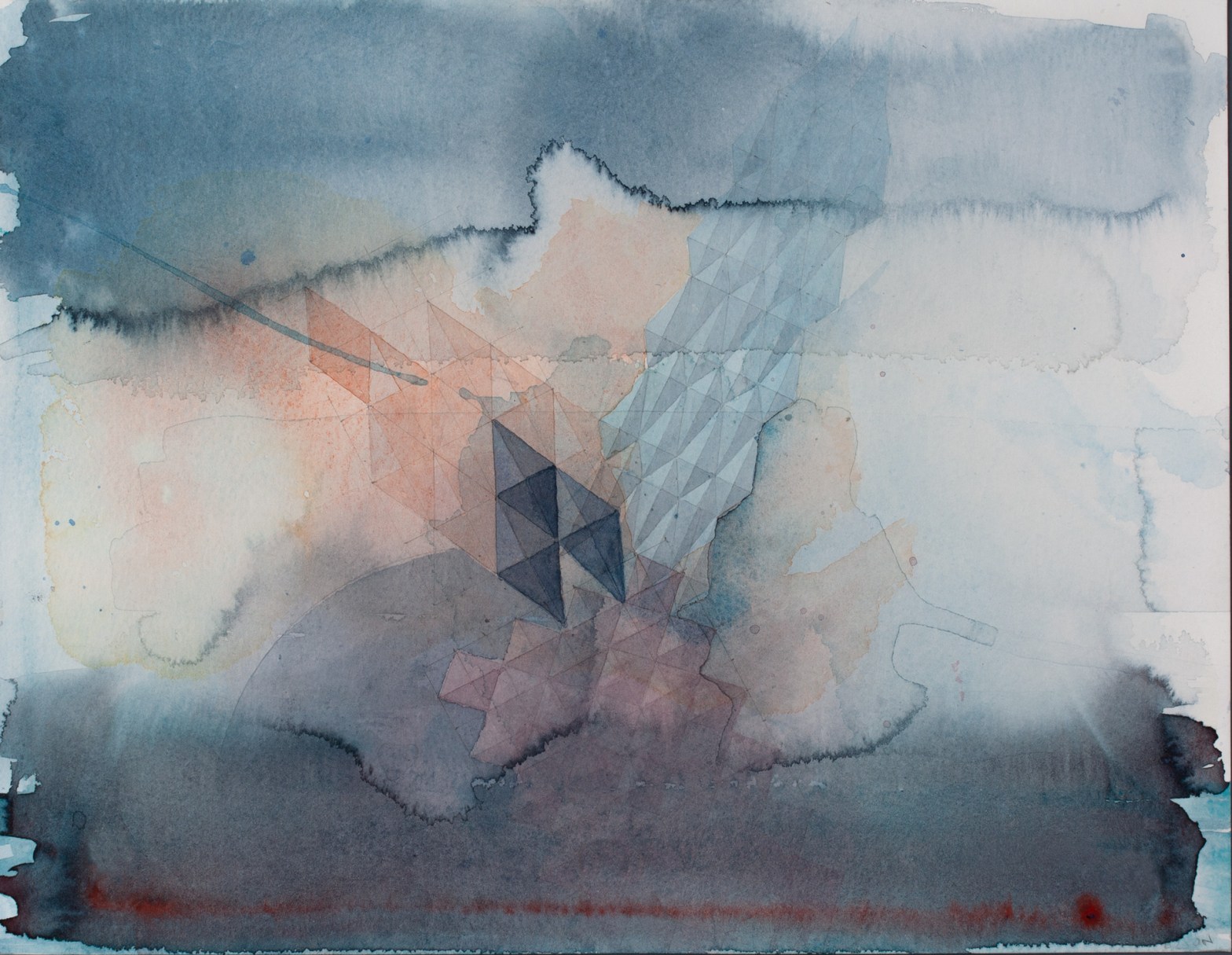

This work is part of a series entitled ‘The Structural Sea’, which engages my fascination with the sea as both place and idea. It takes the building blocks of an eco-system and renders them as symbols and shapes to convey shoals, repetition, direction and encounter. At the same time, angular marks hint at a sense of surveillance from outside.

Watercolour and graphite on paper

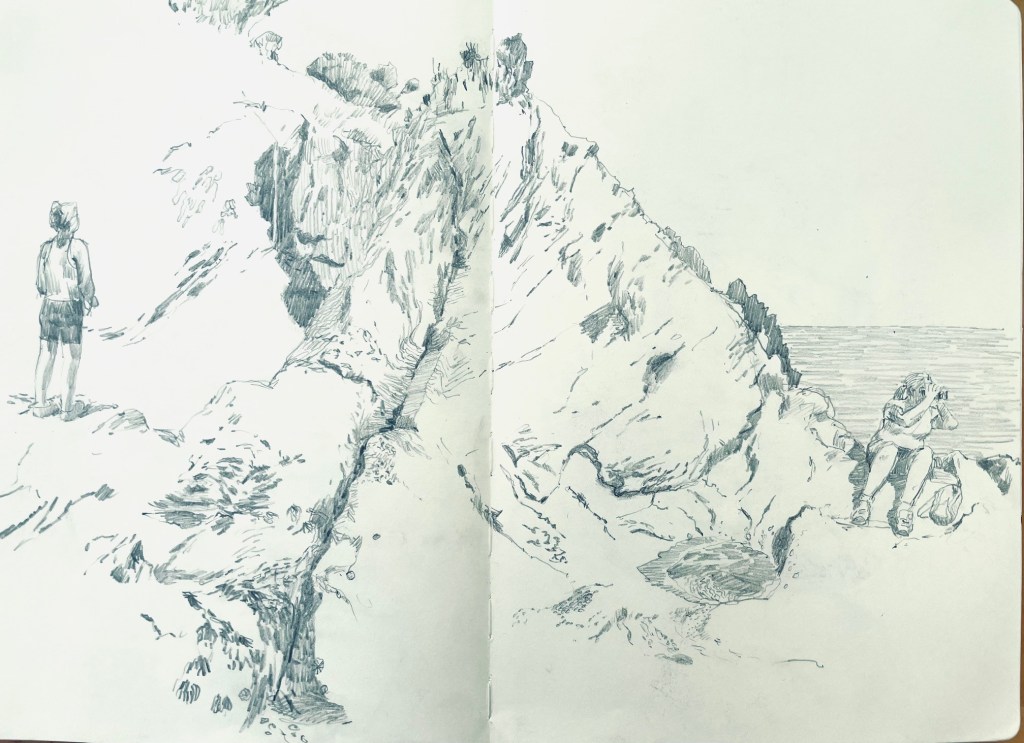

During my residency in Cromarty, I spent a lot of time drawing, without worrying too much about a focussed line of enquiry or subject. Essentially, I just enjoyed the ebb and flow of looking and recording. One evening, we walked across the peninusula to a place on southern side of the Black Isle, called McFarquar’s Bed. I spent a couple of hours lost in drawing the directional complexities of the impressive formations there and two things happened. Firstly, the drawing grew to incorporate a jewel of a rockpool, evaporating above the tidal zone and which I realised would be a good motif and secondly, a cruise liner appeared on the horizon. I have no idea what possible synergy these two things might have, but they seemed right somehow. Drawing at this location held me long enough to allow time for either an event to happen or something to occur in the mind. This small painting – a study perhaps?- was made from the drawings.

Cruise liners visit the Cromarty Firth almost daily during the summer; delivering passengers to Invergordon for the whisky distillery tours. I can’t help thinking that there is something ridiculous about a huge block of flats moving almost silently up the firth and out again. This thought was hardly discouraged by the bizarre experience of hearing the sound of a bingo caller announcing numbers from one of the upper decks as a ship headed back out to sea one evening. Each to their own!

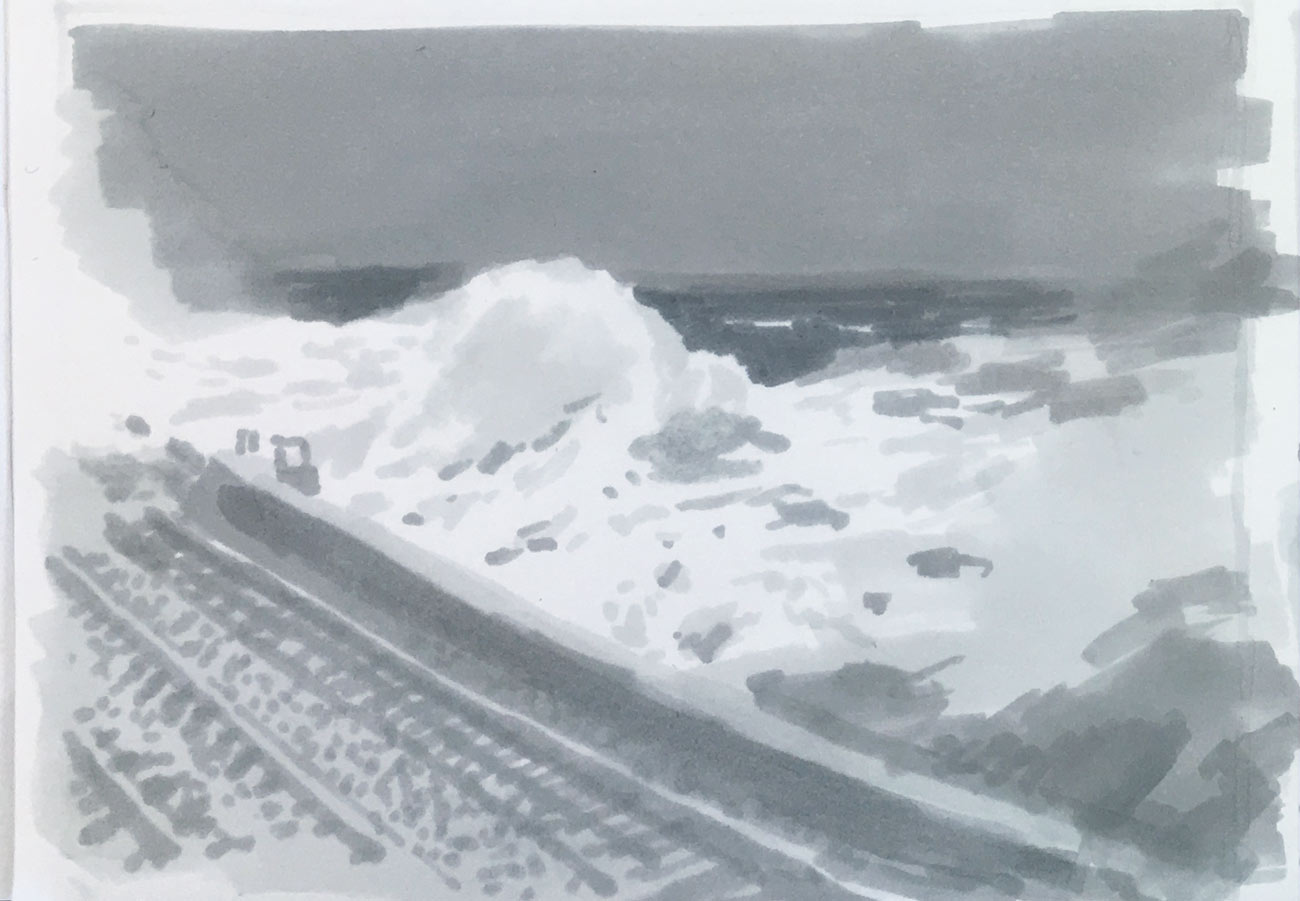

A couple of weeks ago I followed Turner to the end of the Caledonian Canal at Monteith basin. On my phone I had a digital image of the drawings he made there just nine years after its opening in 1822 and I hoped to find some trace of those marks remaining in the landscape. The drawings are cursory and so it is difficult to map them to location. This got me thinking about a distinction between drawing and sketching I hadn’t really c0nsidered before. Previously, I assumed sketching was really just ‘drawing lite’, mostly distinguished by time and fluidity. Working at Cromarty has opened useful threads of distinction between these two close (some would argue, interchangeable) definititions. I think the term ‘drafting’ is probably akin to sketching too, but I might need to (over) analyse that further? Drawing, it seems to me is more deliberately concerned with picture making. When the word ‘out’ is appended to the word ‘sketching’ it seems to take on a different purpose again, to do with learning and knowing something. In other words, sketching is a mode of drawing to do with gathering information that might become knowledge and which, then, is deployed elsewhere. Discuss! Either way, it helped me engage with the landscape in Northern Scotland in different ways – getting lost in mark-making for its own sake, or making visual notes with a view to painting.

Anyway, I found an iron railway bridge near the end of the canal with a red circle painted on the side and made a quick sketch of it, noting some atmospheric conditions, but primarily trying to note the structure of the motif as a way of getting to know it so in a way that I might even be able to recall it verbally, without recourse to the drawing if necessary. Back at the stables I made a small painted study of the scene (above). I think I found Turner in two senses: sketching as ‘knowing’ and his cold burning sun motif, blazing on the side of the bridge.

18 days into a residency in Cromarty, Easter Ross, I set myself an agenda to make drawings and then make paintings from them, without reference to other supporting material, such as photographs. Odd as it might seem, I have rarely made the connection between drawing from life outside and making paintings; generally tending to either paint outside or make work conceptually in the studio. The results are fledgling, but interesting. There is an act of faith in trusting the drawing when it comes to making a painting; accepting the reduced information set and the sense of having left something behind you needed but didn’t realise. This feeds back in to future drawings as experience. The thing I needed to change, was my expectations of what a painting should be and am working towards a more reductive outcome. Drawing feeds the memory with so much more than expected and the slippage between factual reality and invention that results is a satisfying process.

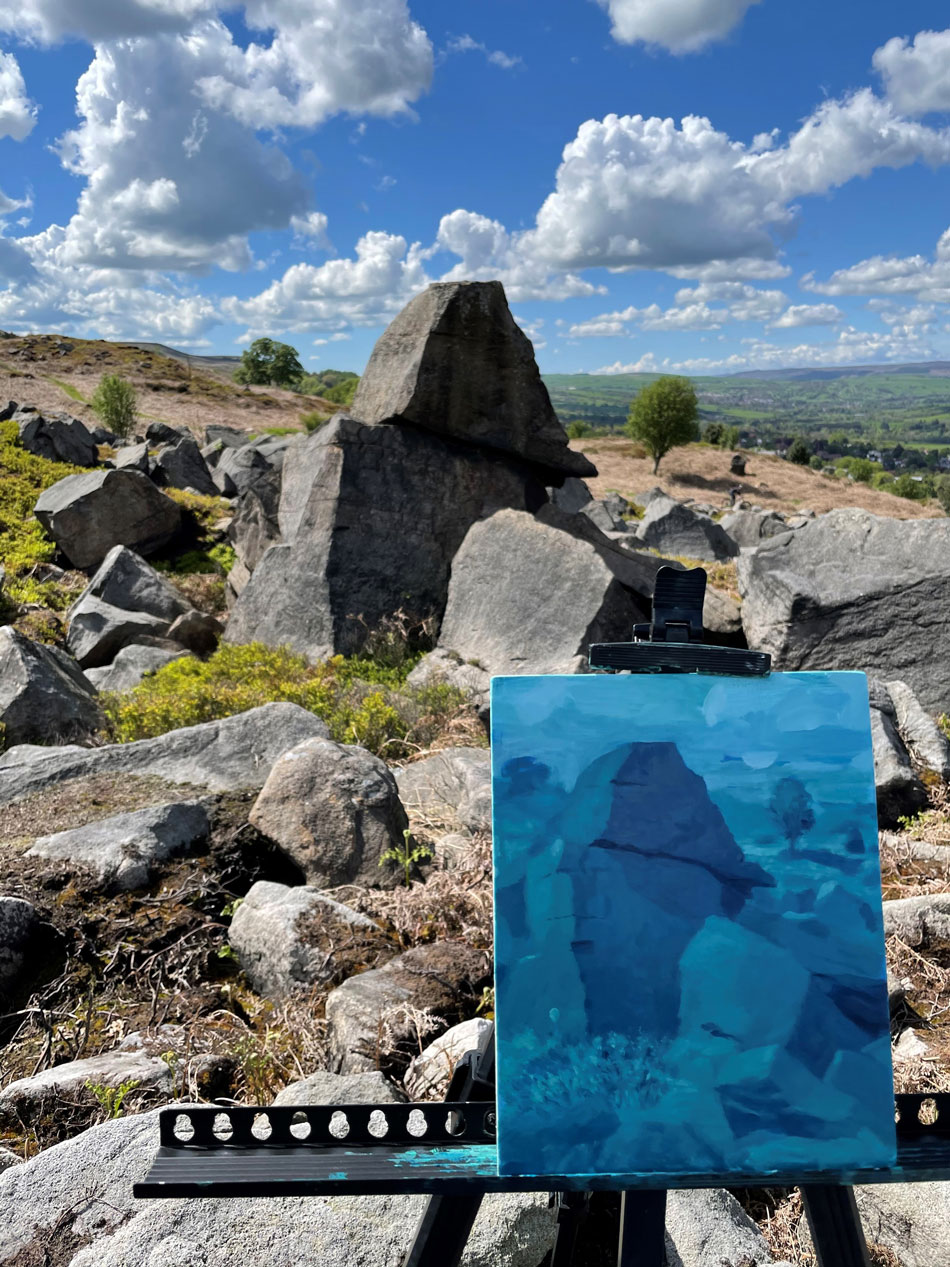

Above Ilkley, near my studio, is a large glacial boulder field marking the end of the moorland plateau. Boulders of different sizes rest alone, like monoliths or in clusters, sometimes piled improbably upon each other. The hard gritstone has few natural faultlines, but where broken or cracked, the parting often follows a straight edge. Although I’ve known this landscape all of my life, it took the restrictions of lockdown to cause me to revisit it with fresh eyes.

I realised after a while that I was making these paintings in a vertical, or portrait, format – a preference I’ve applied almost exclusively lately – and that this led to a thought that, perhaps, these are portraits. They are certainly cropped closely and any contextual expanse is minimal. For recognition purposes I had already started naming these rocks by their apparent (to me at least) characteristics: Split Rock, The Axe, Locomotive Rock (in memory of my Dad), Wizard’s Hat Rock etc. etc. Naming these gritstone blocks reminded me of my (very moderate) rock climbing days, where cliff features were named by their conquering rock climber heros. In nearby Ilkley Quarry is an arete route up an unforgiving gritstone block named ‘The New Statesman’ graded E9 (E nine) and first climbed by Jon Dunne in 1987., who’s shop on Manningham Lane I used to buy climbing gear from. It is still one of the hardest rock climbs put up on gritstone in the world.

I am showing work at 5 Bold Place, run by Art in Windows, Liverpool in the month of June 2019. The work echoes the maritime setting of the city and contains a cheeky, but ultimately respectful, reference to Peter Blake’s Razzle Dazzle ferry.

June 2nd-29th

5 Bold Place, Liverpool, L1 9DN